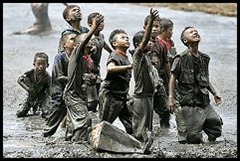

In 1991, Goldman Sachs decided that food might make an excellent investment. By then, nearly everything else had been recast as a financial abstraction that could generate wealth without risk, so the analysts transformed food. They selected eighteen commodifiable ingredients and contrived a financial elixir that included cattle, coffee, cocoa, corn, hogs, and a variety or two of wheat. They weighted the investment value of each element, blended and commingled the parts into sums, then reduced what had been a complicated collection of real things into a mathematical formula that could be expressed as a single manifestation known as the Goldman Sachs Commodity Index, and began to offer shares. This was a new form of commodities investment that eliminated the complexities of the commodities themselves. It allowed investors to park a great deal of money somewhere, then sit back and watch it grow, without any of the risk that the bankers themselves had introduced into the market.  In fact, the mechanism of long and short selling, that had been created to stabilize food prices, now had been reassembled into a mechanism to inflate those prices. If the price of a commodity went up, Goldman made money, not only from management fees, but from the profits the bank pulled down by investing 95% of its clients money in less risky ventures. They even made money from the roll into each new contract, every instance of which required clients to pay a new set of transaction costs. As a result, the prices of all these “elements”, cattle, coffee, corn, wheat, etc., began to rise. And because it was successful, other bankers created their own food indexes as well. So, by the first quarter of 2008 transnational wheat giant Cargill attributed its 86% jump in annual profits to commodity trading. In fact, this global speculative frenzy in food commodities raised prices of food so dramatically that it sparked riots in more than thirty countries and drove the number of the world’s “food insecure” to more than a billion people. The ranks of the hungry had increased by more than 250 million in a single year, the most in all of human history. In reality, more than a billion people could no longer afford bread.

In fact, the mechanism of long and short selling, that had been created to stabilize food prices, now had been reassembled into a mechanism to inflate those prices. If the price of a commodity went up, Goldman made money, not only from management fees, but from the profits the bank pulled down by investing 95% of its clients money in less risky ventures. They even made money from the roll into each new contract, every instance of which required clients to pay a new set of transaction costs. As a result, the prices of all these “elements”, cattle, coffee, corn, wheat, etc., began to rise. And because it was successful, other bankers created their own food indexes as well. So, by the first quarter of 2008 transnational wheat giant Cargill attributed its 86% jump in annual profits to commodity trading. In fact, this global speculative frenzy in food commodities raised prices of food so dramatically that it sparked riots in more than thirty countries and drove the number of the world’s “food insecure” to more than a billion people. The ranks of the hungry had increased by more than 250 million in a single year, the most in all of human history. In reality, more than a billion people could no longer afford bread.  The worldwide price of food had risen by 80 percent between 2005 and 2008, and unlike other food catastrophes of the past half century or so, even the United States was not insulated from it as 49 million Americans found themselves unable to put a full meal on the table. Across the country, demand for food stamps reached an all-time high, and one in five children came to depend on food kitchens. In Los Angeles, nearly a million people went hungry. In Detroit, armed guards stood watch over grocery stores. Even the New York Times and other mainstream media outlets admitted that rising food prices had, “played a role” in the catastrophe. And this year, the hedge fund manager of AIS Capital Management wrote that “the fundamentals argue strongly” that commodity prices could advance “460% above the mid-2008 price peaks.” That would put the price of a pound of ground beef at $20. When asked if he thought that were true, the chairman of the Minneapolis Grain Exchange responded, “absolutely.” This is what it means to leave “the market” unfettered: most of us are starved so 1% of the world’s population can become immeasurably more wealthy.

The worldwide price of food had risen by 80 percent between 2005 and 2008, and unlike other food catastrophes of the past half century or so, even the United States was not insulated from it as 49 million Americans found themselves unable to put a full meal on the table. Across the country, demand for food stamps reached an all-time high, and one in five children came to depend on food kitchens. In Los Angeles, nearly a million people went hungry. In Detroit, armed guards stood watch over grocery stores. Even the New York Times and other mainstream media outlets admitted that rising food prices had, “played a role” in the catastrophe. And this year, the hedge fund manager of AIS Capital Management wrote that “the fundamentals argue strongly” that commodity prices could advance “460% above the mid-2008 price peaks.” That would put the price of a pound of ground beef at $20. When asked if he thought that were true, the chairman of the Minneapolis Grain Exchange responded, “absolutely.” This is what it means to leave “the market” unfettered: most of us are starved so 1% of the world’s population can become immeasurably more wealthy.

No comments:

Post a Comment